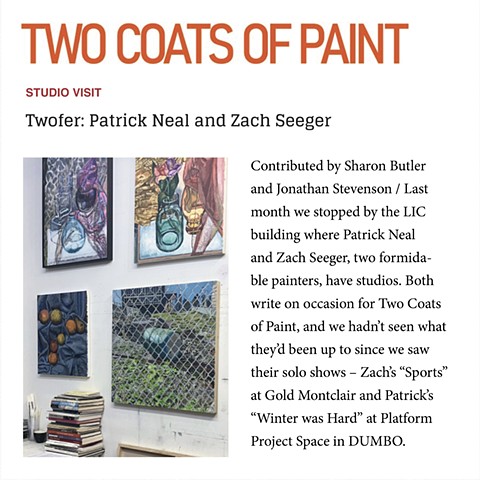

Twofer: Patrick Neal and Zach Seeger

After founder’s death, Joyce Goldstein Gallery hosts final show

Artists celebrate Goldstein Gallery, closing in January

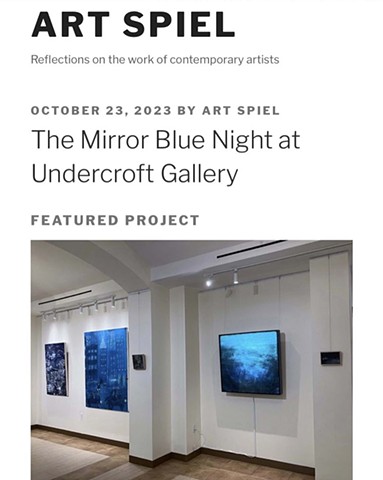

The Mirror Blue Night at Undercroft Gallery

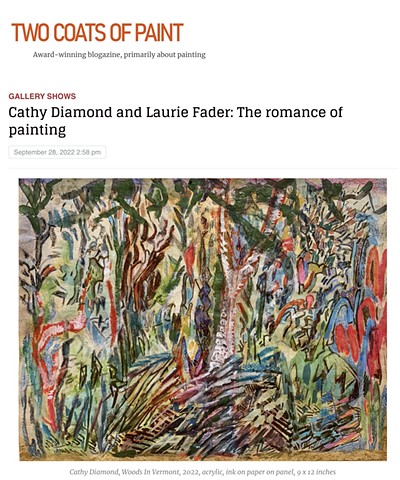

Cathy Diamond and Laurie Fader: The romance of painting

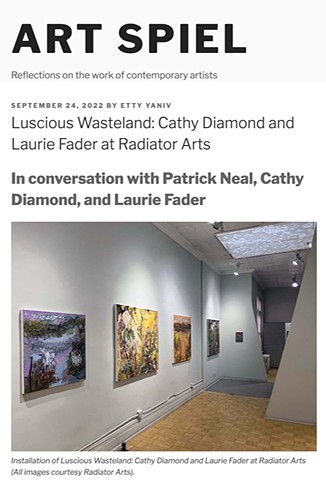

Luscious Wasteland: Cathy Diamond and Laurie Fader at Radiator Arts In conversation with Patrick Neal, Cathy Diamond, and Laurie Fader

Hyperallergic / In Long Island City, Local Artists Go Big and Bold

“ArtBeat Report” on The Bill Newman Show on WHMP Radio, October 2019

whmp.com/podcasts/shows/bill-newman/?fb…

by Donnabelle Casis, October 2019

On the ArtBeat Report this morning: TONIGHT The ArtSalon goes to Conway; HUT XXV: Words, Sound, Movement, Saturday in Northampton at Studio4 School for Contemporary Dance and Thought; Next Tuesday Peyrelebade Patrick Neal Reception at the Oresman Gallery at the Brown Fine Arts Center Smith College: Art(Stops) in Springfield put on by the Springfield Central Cultural District . Listen live around 9:50am!

The 2018 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowships on Two Coats of Paint

Birds of America: Explorations of Audubon The Paintings of Larry Rivers and Others

Patrick Neal at the Chocolate Factory

Patrick Neal / Floors and Walls-New Paintings

The Chocolate Factory, Long Island City, NY, May 2007By Rick Whitaker

If, as Clive Bell wrote in his early-20th-century essay "The Debt to Cézanne," that greatest of modern painters invented an instrument on which later artists may "play their own tunes", Patrick Neal has fashioned from it a prepared piano in which nuts and bolts and rubber bands are placed inside the grand piano making sounds newly strange, exotic, and fresh, enabling the composer to indicate with a conventional notation a panoply of noises that evoke the gamelan, music we in the West will never fully understand or appreciate, however much we may love its exhilaratingly chaotic-sounding productions. What we love most about the Tibetan sound is precisely its otherness, its distance from our own sound-world, and likewise one of the aspects of Patrick Neal's paintings is the sense they suggest of distance from an ordinary pictorial relation to the object. It's music, but it's not diatonic or modal or even serial. The harmonic gestalt is unique.

As I write this, I can hear 'music' from the simplest and folksiest of 'instruments,' a homemade wind chime bought years ago on a summer day from a farmer who had fashioned it from spoons, an ingenious little contraption that makes the sweetest sounds I know, the easy relation between weather and metal reminding me of the outdoors, of the wind, of the farmer, of summer, of the years gone into the past. Similarly, Patrick Neal's pictures evoke the natural world that lies behind Cézanne; they suggest both Aix-en-Provence and the unsettling aftermath, the world since Cézanne. By having come so close to his precursor, it's as if Neal has gone madly into the arena, and his paintings are the record of a struggle that is meant to disturb. The spectators want to see blood shed, and Neal's agon with Cézanne gives it to us in one picture after another. Painting for Neal is frankly competitive and ruthless, he tears off a piece of the past and masticates it before our eyes. It’s exhausting and endless work. There is no clean success, no ultimate victory, there is no hope of overcoming or subduing the master, just as no writer has ever seriously entertained the feasibility of matching, let alone overtaking, Shakespeare’s breadth and depth. Writers do not even attempt it, it is a hopeless impossibility. And so it is with Cézanne, on whom no painter could conceivably improve. One is forced to do something else. Coping with his work of a century ago, for a certain kind of painter, is a shaming prospect. Thus the excitement we feel witnessing an artist like Patrick Neal's originality oozing out from the desiccated sac of the history of art. His paintings are re-inventions or re-visions, astonishing re-figurations of what cannot be other than already-seen. The paintings suggest that we are nearing the end of re-seeing, that these pictures have eked out whatever life is left in the particular kind of seeing known as painting. Perhaps it has always been so, perhaps Cézanne’s paintings appeared similarly final a hundred years ago in their statement of what the artist is capable of doing with pigment on a flat canvas. But there is something vertiginous about imagining a painter grappling, a hundred years from now, with Patrick Neal's bloody, battle-worn works of art.

Tastes of Mingled Palettes

*Living Arts

The Boston Globe, Thursday, June 23, 1994

Tastes of Mingled Palettes

By Nancy Stapen*New Talent at Alpha Gallery, 14 Newbury Street, through July 8

For the buyer willing to go with his or her intuition, this is a great time of year to visit the galleries. Those with less-than-deep pockets can benefit from the crop of "new talent" shows, those yearly rituals at which galleries try out new artists with highly affordable price tags. Some of these hopefuls go on to artistic prominence; others disappear into obscurity. In any event, the wise buyer concentrates on finding that obscure object of desire.

The sovereign site of new talent is the Alpha Gallery, which is holding its record-breaking 26th annual New Talent show. Among the well known painters who premiered here are John Moore, Francis Gillespie, Richard Sheehan, Aaron Fink and Scott Prior. This year's group of five is a mixed bag; yet, though their styles vary, all are concerned with nature and organic form. They include older and younger artists; among the former is Beverly Floyd. Her abstract oils and collages of striped elongated forms, often labeled "Floating Gourds," evoke such natural phenomena as tadpoles or muscle tissue. Lodged in wide horizontal bands of muted color and partially obscured by gauze, tissue or blurred paint, they are veiled and elusive. They suggest something coming into being, or thoughts emerging to consciousness.

In Dennis Crayon's collaged fresco-like paintings, past and present collide. Seeming to be crumbling ancient fragments, the images are created via photostatic transfers onto plaster. Eggs and bunches of grapes are frequent motifs, combined with images of architectural sites, what appear to be computer chip patterns and (sometimes actual) tools. Some of the images of eggshells seemingly dematerializing are particularly effective; they evoke life's fragile beginnings.

Nature is fragile yet stalwart in Judith Bowerman's low-key monotypes of single plants, flowers or trees, which delicately explore aspects of texture and color. A seemingly gray-brown palette is leavened by pale yellow, and undertones of pink and magenta. The attenuated, isolated forms are offset by Bowerman's confident contours. She is an artist who doesn't shout, but hums.

By contrast, Patrick Neal's oil paint still lifes are busy with patterns derived from Islamic and Asian cultures. Still, their earthly rusts and greens maintains a muted mood. Neal tilts his objects upward; this spatial play is futher complicated by the regularity of the patterns played off against the lush leaves of randomly proliferating plants. In "Still Life With Islamic Pattern" the leaves curl near a vase painted with floral designs, a fluid meeting of nature and culture. Neal's images suggest that the 70's movement known as Pattern and Decoration is still alive for young artists.

The youngest artist and only sculptor, Bethany Bristow (who graduates from the Museum School this year), works in glass and mixed media. Bristow melts and distorts bottles in a kiln, creating objects reminiscent of the body, with a curious mix of tensile strength and enervation. Rope binds the forms, or, in works like "Bleed," emanates from the bottles' "orifices," suggesting seeping body fluids. Kiki Smith and Eva Hesse are clearly influences, but Bristow gives every evidence of developing a strong subjective voice.

............................................................................